The Norman Conquest

- Dickie66

- Oct 1, 2021

- 20 min read

Updated: Nov 13, 2021

No, not that one!

I never really enjoyed history lessons at school. Maybe it was the subject matter, maybe the teacher. Anyway, I dropped the subject at 13 years old, before ‘O’ level. But now I love history and would have loved to study it more. I never really had (i.e., never made) the time, when I was working.

I’m sure that my experience is not unique. It’s one reason why I think that some education is wasted on the young. They are also often simply too young to appreciate the learning points from the subject. To my mind, it would be better to give schoolchildren a few ‘education-vouchers-for-life’, that they could cash in during their working career. I would have loved to have had a history voucher, which I could have used during 6-months unpaid leave, whilst receiving a basic state income. They could spend their lessons up to Year 9 learning more practical stuff. You know, nuclear power engineering, HGV driving etc…

While reading various books in Aubeterre, I have been looking for a connection to our next sailing destination: Sicily. This is simply an excuse for writing a new blog, that actually relates to our nautical adventure. As a child, one of my favourite programs was James Burke’s ‘Connections’. [Alix: Oooh, I liked him and he was quite dishy too, wore black a lot] Burke questioned the linear view of history and innovation, and he proposed instead, that the modern world is the result of a web of interconnected events, each one with no prior concept of the final outcome.

Could I find a connection between Aquitaine, where I sit now, and Sicily? The answer is, not really. Or that the examples I found are a bit spurious.

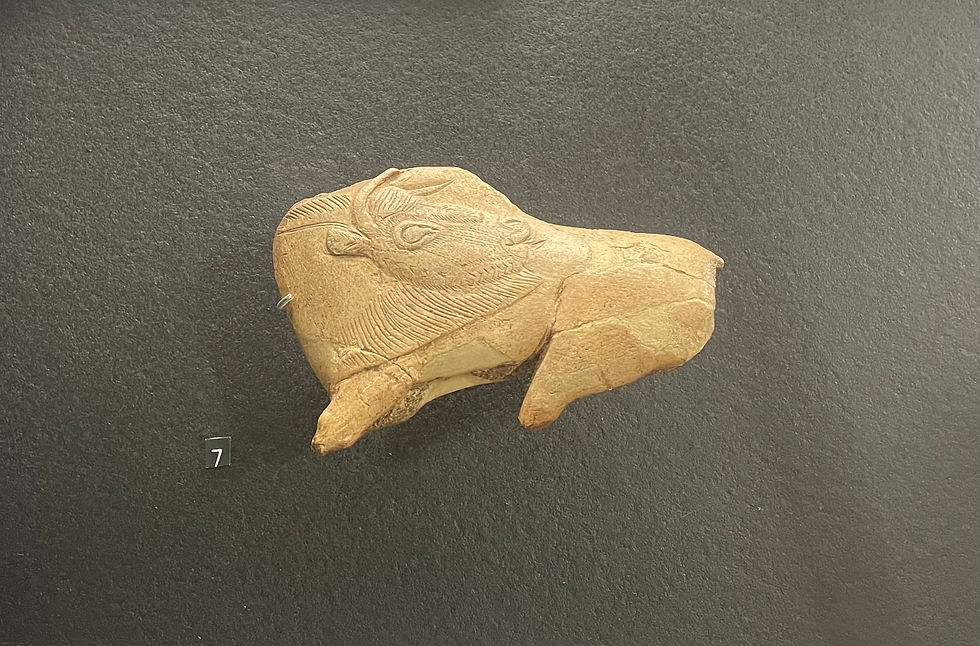

For example, we visited the Musée National de Préhistoire in the Vézère valley this week, to search for a specific artefact that was discovered at the troglodyte village of La Madeleine, that we had visited the previous week. The artefact is an exquisite stone-age carving on reindeer antler, of a bison licking its flank. It is a remnant part of an arrow-thrower.

During our visit, we passed a display showing the possible migrations of early Homo species from east Africa. As well as the well-known exodus route through the Arabian Peninsula, other possible land bridges might have existed between Africa and Spain (near Gibraltar), and also between Africa and Italy (via Sicily). I think this theory is now also backed up by genetic analyses. It got me wondering whether the ancestors of that early hominid carver in France had migrated through Arabia, Spain or Sicily?

See, I told you it was tenuous! James Burke would have thrown out the idea out without a second thought.

I was more successful, however, in finding a connection between dear old Blighty and modern Sicily, thanks to a wonderful book called ‘The Normans in the South’, by John Julius Norwich. I’ll embellish below, but if you are not interested in how fecundity, greed, opportunism, brigandry, theft, cunning, bribery, deceit, religion, and other such vices shaped our world, then stop reading now!

The Connection: Harold Hardrada

One fact that I do remember from my junior school history lessons is the main reason why Harold Godwinson (King Harold II) lost the Battle of Hastings to the Norman, William I. No, not the arrow in the eye! I remember that Harold and his army were probably exhausted, following their forced-march up to Yorkshire and back, to fight off another Norseman, who claimed the English crown, called Harald ‘Hardrada’ Sigurdsson. That battle took place at Stamford Bridge, where we often stopped in the ‘70s enroute to our annual family holiday to Scarborough.

The story at school leapt quickly back to William the Conqueror, who had sailed from French Normandy. The Normandy fiefdom had been allocated to his Viking Norsemen forebears by the King of the West Franks (the French) in 911, simply to keep them under control.

But what of Harald Sigurdsson? Who was he? I don’t remember school lessons covering that.

After a royal power struggle in Denmark and Norway in 1030, Harald was exiled. He travelled to Constantinople, via Kievan Rus (modern Belarus, west Russia and Ukraine), a land then ruled by the Varangians. He joined the Varangian Guard in Constantinople, which was an elite unit of the Byzantine Army, serving as personal bodyguard to the emperor of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. Apparently, the emperors liked mercenaries, such as Norsemen and Anglo Saxons from England, because they had no local political loyalties and could be relied upon to suppress local revolts.

The Byzantines sent an expedition in 1038, led by the Greek George Maniakes, to recapture Sicily from the Muslim Saracens. Harald served in that Byzantine force. Co-incidentally, he was fighting alongside Norman mercenaries who were also on the Byzantine payroll, or at least expecting some spoils of war.

That this invasion was ultimately unsuccessful is of no consequence to this story right now, but that connection – the meeting in Sicily of two distinct tribes of Viking mercenaries – led me to ask how that happened. And how it happened nearly 30 years prior to the Norman conquest of England, and nearly 60 years before the First Crusade.

Norman Qualities

We have skimmed over Harald’s route to Sicily, but what of the Normans’ route? This is where I précis Norwich’s excellent, scholarly book. First, as some background, it seems to me that the Normans had some qualities, that explain a lot of what happened next:

I) they were pretty fecund, i.e., they had lots of (male) offspring;

II) the first heir seemed to inherit all the existing assets, leaving younger siblings to be provided for;

III) they were materialistic warriors, not innovators or administrators (bar collecting taxes from the serfs). In other words, they didn’t grow wealth, but searched for it and took it by force, which they were ruthlessly good at;

IV) despite their internecine squabbling, they identified and stuck together as French-speaking ‘Normans’;

V) they were opportunistic and quick to spot, or break, alliances, as it suited them;

VI) they tended not to pick a fight that they couldn’t be confident of winning; and

VII) latterly they liked legal systems, because they could make laws that suited them, in the knowledge that most serfs will adhere to laws;

VIII) they were newly Christians, even perhaps God-fearing, in so much as they could ultimately try and avoid hell.

A Rootless Beginning

And it was the last point that explains why the story starts with a semi-mythical event in 1016, at the shrine at Mount Gargano in Apulia (the heel/Achilles of southern Italy).

I have based this blog on Norwich’s epic story, and simplified it a lot!

About forty Norman knights were visiting the shrine [Alix: You can imagine it, beer, T-shirts saying ‘We’ve Been on a Pilgrimage’, with dates on the back], on their way home from their main pilgrimage to Jerusalem, when they were approached by a Lombard man called Melus. Much of southern Italy had been re-captured from the Ostrogoths by the Byzantine Empire, under Macedonian leadership. But the land had been heavily populated by a new wave of Germans - the Lombards (‘long beards’). Melus was a Lombard of southern Italy, and a Lombard nationalist. He wanted rid of Byzantine rule with their heavy taxes. Would the Normans help him?

The Normans could not resist the opportunity, as it suited most of their innate qualities, including a narrative of ridding the area of non-Latin church. But as pilgrims they were not fully armed, so they first rode to Normandy to collect arms and to recruit some of their young male relatives. They returned in the summer of 1017, and a year later had helped the Lombards drive the Greeks from the area. But the Greeks returned, this time with their infamous Varangian Guard in support, and defeated Melus’ Lombards.

The Normans, demonstrating their form, looked instead to new Lombardian paymasters, and some even joined the payroll of the occupying Greeks. Self-interest drove them, there being no sense of a Norman ‘nationality’ at that time, as there were so few of them. As we will see, the Norman groups morphed and changed alliances. They tried to back the winning faction in any local rivalry, whilst maintaining their freedom.

The Greek occupation worried the Pope in Rome (Benedict) and the German Holy Roman Emperor (Henry II). For example, the Greeks had captured one city and killed all the Lombard resistance. Interestingly, the Norman contingent was spared, possibly at the behest of the Normans fighting on the Greek side. This was not a one-off; ultimately the Normans looked out for their own.

In 1021, Henry II launched a campaign southward against the Greeks. This proved inconclusive, largely because of stand at Troia by the Normans, which saved the whole of Apulia for the Greeks. Equally, Henry was grateful to other Normans for helping him capture Capua (near Naples), and imprisoning its prince, Pandalf (the Lombard ‘Wolf of Capua’). The Normans had mastered the art of being on the winning side.

Henry’s successor, Conrad II, was less interested in southern Italy, and for some reason approved the release of Pandalf. The Wolf immediately set about asking for help to recover Capua. A Norman group, led by Rainulf, offered assistance and was instrumental in helping a Greeks force (under Boioannes) to besiege and capture the city for Pandalf. The city folk suffered vengeance, but the Norman garrison was spared, probably at the request of Rainulf.

In 1027, Pandulf continued to gain more territory, made possible by the departure of both Holy Roman and Byzantine forces, to fry bigger fish elsewhere. He took Naples taken from Sergius.

The First Foothold

The Wolf knew that he was not a well-liked prince and needed Norman muscle to consolidate his gains. He approached Rainulf whose band was the largest, with new recruits constantly arriving from ‘home’. But Rainulf realised that an all-powerful Wolf would not serve Norman interests in the long-term. So, he switched sides and helped Sergius retake Naples in 1029.

As a reward, in 1030, Sergius granted Rainulf the town and territory of Aversa (just north of Naples), and also his sister’s hand in marriage. This was a key moment for the Normans: it was first fief of their own, 13 years after their arrival in Italy to help Melus. This sowed the idea of them becoming established landowners, rather than just being rootless brigands for hire.

It did not affect their behaviour, however: Rainulf showed immediate treachery by switching sides when his wife (Sergius’ sister) died. He accepted the Wolf’s offer of his niece’s hand in marriage, along with more land at Amalfi. Sergius, realising he had been betrayed, left Naples to live in a monastery.

The Wolf’s greed and bad behaviour, even against the monasteries, caused Emperor Conrad II to return in 1038 to deal with him. Cleverly, Rainulf shifted allegiance again, this time to Gaimar, Prince of Salerno. Together they helped Conrad defeat and expel the troublesome Wolf. Rainulf was again on the winning side, and better still, before he left, Conrad granted Rainulf a title: Count of Aversa (a vassal of Gaimar, who was himself now Prince of Capua and Salerno). The Normans had climbed another rung up the ladder.

Gaining Land and Titles

Tancred, a Norman from Hauteville on the Cherbourg peninsula, had twelve(!) sons by two wives. In 1035, the first of them rode to Italy seeking the promised opportunities. They watched how Rainulf operated, and they learned well.

Meanwhile, the Byzantine Greeks were plotting to retake Sicily – what they believed to be their birth-right - from the occupying Muslim Saracens. [This was the campaign of 1038, that Hardrada took part in.] Their general, George Maniakes, first stopped in Salerno to ask for help from Gaimar. Gaimar was starting to have problems managing the young and restless Normans, so he readily offered up 300 of them - including the Hautevilles- to be led by a Lombard called Arduin. After early successes, Maniakes had Arduin stripped and beaten for not giving him a captured horse. The campaign ended prematurely when Maniakes was recalled to Constantinople.

Back on the mainland, Arduin - now hating the Greeks after his public humiliation - gathered his 300 Norman knights at Melfi to drive the Greeks from Italy. They had three consecutive successes in Apulia. Maniakes was sent to tame the rebellion, but was rebuffed.

Despite these gains, the Lombard rebellion suffered from infighting. In 1042, Melus’ son, Argyus – and not Arduin - was chosen as their leader. Strangely, Argyrus immediately defected to the Greeks, possibly due to a huge bribe, or that he had grown mistrustful of the increasing power and influence of the Normans.

Fed up with Lombard infighting, the Normans decided to elect their own leader. William ‘Iron Arm’ – Tancred’s third son - was duly elected. They titled him a count, but to formalise any title, William needed a suzerain. Gaimar consented and was himself proclaimed by the Normans as ‘Duke of Apulia and Calabria’. He gifted individual Norman chief other lesser landed titles (baronies), including of land yet to be conquered. William ‘Iron Arm’ was confirmed as ‘Count of Apulia’. The Normans were now entrenched and legalised, albeit not yet ratified by the ultimate suzerain, the Holy Roman Emperor.

Papal ‘Recognition’

In 1046, new Normans were still arriving from France. They included Richard (Rainulf’s nephew), and Robert de Hauteville (Tancred’ sixth son, and eldest of his second marriage), later to be known as ‘Guiscard’ – the ’Cunning’.

Drogo had succeeded his older brother William ‘Iron Arm’, but refused to ennoble his brother Robert, nor give him land, for fear of upsetting more deserving local Normans. Eventually, he sent Robert to command one of the garrisons in Calabria, established following a recent expedition. Robert survived, as Normans did, through brigandry: they simply took by force or ransom from the coastal Greek population, including monasteries. Richard was not given a free lunch either, so he made a nuisance of himself, living off his wits, until he eventually was acclaimed Count of Aversa, following his uncle Rainulf’s death.

The Normans’ behaviour made them increasingly unpopular with the local Italo-Lombards, the Greeks and the neighbouring papal states. So much so that Drogo was assassinated, and his suzerain Gaimar was also murdered. But that just made the Normans angry.

Missives were sent to the Pope and Holy Roman Emperor to intervene against the Normans. Eventually, in 1053, Pope Leo managed to assemble a combined German and Italian army (without the emperor’s help), and marched south. He intended to join a Byzantine force heading north through Apulia. The Normans, led by Humphrey de Hauteville (succeeding his brother Drogo), included Robert Guiscard’s knights plus those of Richard of Aversa. They met the papal army at Civitate, and preventing the Pope rendezvousing with the Greeks. The Normans scored a decisive victory, and - slightly embarrassed that they had fought the Vicar of Christ - escorted Leo back to Benevento. They only released him once he had formally recognised all the Norman conquests to date. Civitate was as significant to the Normans as Hastings would be thirteen years later!

The Normans (Guiscard specifically) realised their strong position and made impressive gains in Apulia and Calabria. Humphrey de Hauteville died in 1057, and his brother Robert Guiscard succeeded him continuing his ways alongside his Norman rival, Richard.

Both eastern and western churches knew they must work together to stop Norman ascendency. But they had significant religious differences, and in 1054 they achieved lasting separation: the main issue was the filioque, whereby the western church adapted the Nicene Creed to make Jesus, as well as God, an origin of the Holy Spirit! The east could never agree to it!

Pleas for relief from Norman rule continued to be sent to Rome. But the western church was also embroiled in an internal row. Two rival factions existed: the old guard elected Benedict X; but the reformists elected Nicholas II. The reformists wanted Papal supremacy, and for Cardinals to elect the Pope without requiring the emperor’s approval. The reformists won the first battle and Benedict X was expelled from Rome as the ‘Antipope’.

The reformists then, remarkably, asked the Norman’s for help and Richard agreed; He led 300 knights to Rome, and helped to capture and imprison Benedict. A Norman-Papal friendship had begun. Nicholas went to south Italy in 1059 to confirm Richard as ‘Prince of Capua’. He also confirmed Robert as ‘Duke of Apulia, and of Calabria and of Sicily’ (!), even though Robert had never set foot there.

A Foothold in Sicily - The arrival of Roger [Alix: Welease Woger!]

From the title the Pope had invested in Robert, it was clear that a Papal objective was to throw the Muslim Saracen pirates from Sicily. The Pope could not rely on an imperial army, but he had recruited the Normans instead!

And still more Normans arrived. In 1057, Tancred’s youngest son, Roger, arrived in Calabria and went under Robert’s wing. Roger de Hauteville was as capable as his brother, and together they cleared up some remnant Greek cities, before focussing across the Straits of Messina at their island prize. They hoped that the significant Christian population would be sympathetic, and they knew that the three Emirs were infighting, so that alliances could be made.

But, what at first sight looked like a straightforward conquest, would eventually take thirty-one years. There were several reasons:

First, Apulia was not totally secure from Byzantine sorties;

Second, their Calabrian vassals and serfs rose continually in rebellion. This meant the Normans were always fighting on two fronts, which eventually led to Robert to focus on the mainland, leaving Roger to focus on Sicily;

Third, although they could win individual sieges and battles, the Normans lacked numbers, so they could not hold their wins, whilst advancing to take the next city. The Sicily campaign also depended upon a bridge-head and secure supply line back to Calabria;

Fourth, not all the island Christians regarded the Normans as being better potential masters than the Saracens; and

Finally, the Normans had no navy, which was severe handicap when trying to besiege coastal towns on an island.

Roger’s campaign began properly in 1061, when one of the Emirs – Ibn al-Timnah - asked him to come to his assistance. Roger had a couple of early setbacks, but he took Messina the following year, before Robert arrived with help. With their friendly Emir, they headed westwards towards Enna, the stronghold of Emir Ibn al-Hawas.

Even the Saracens had struggled to take Enna from the Greeks, and only then by crawling one-by-one up the main sewer. Instead, Roger managed to coax the Saracen army from the city and routed them in the field. The hostile Emir remained safe in the citadel, and watched on as the Normans scorched his lands, plundered and frightened his people into paying homage to them. The siege of Enna failed, and many Normans returned to their mainland homes for the winter. But crucially, some remained and built the first Norman castle on the island at Aluntium.

Because Roger was so capable, Robert had become jealous of his ambitions. The brothers’ quarrels delayed their Sicilian campaign. One quarrel regarded inheritance. Robert had only a bastard son, Bohemund, so in 1058 he married a formidable Lombard warrior called Sichelgaita, who bore him eight children, including three male heirs. In 1062, Roger also took a wife, his childhood sweet-heart, Judith of Evreux. She was the daughter of a first cousin of William the Conqueror. Robert did not want Judith to have a dowry (knowns as a Morgengab) upon Roger’s death, that might give her Sicily. Roger was furious, but won the ensuing fight with his brother.

Roger returned to Triona in Sicily with Judith to find that his Emir ally had been assassinated and the whole situation was unstable. While Roger was away on a sortie, the local Greeks rebelled and tried to capture and ransom Judith. Roger returned in time, but the Normans were now besieged by both Greeks and Saracens. The Normans held out over the long, cold winter, even eating their own horses [Alix: We have a cheval butcher in our local town]. At the point of starvation one cold January night, he attacked the Muslim Saracens sentries who were asleep after drinking local red wine. Troina was re-taken.

Sicilian Crusade

After plundering new supplies and horses, the Normans re-grouped and then won a decisive battle at Cerami, against a combined and much larger Saracen army. Roger sent four captured camels to the Pope in Rome (now Alexander II). In return, Alexander sent Roger a papal banner, and absolved anyone who joined Roger and Robert in Sicily, in what was now effectively a Crusade.

At this point Pisa, annoyed by ongoing Saracen piracy, appealed to Roger for land-based assistance if the Pisan fleet sailed to capture Palermo. Roger declined; perhaps he wasn’t ready, or maybe he did not trust the Pisans’ long-term objectives. Instead, in 1064 and with Robert’s help, the Normans headed straight to Palermo and besieged it. It was to no avail, however, as without a navy the Normans could not prevent the free-flow of shipping into the harbour.

Momentum was lost, and four quiet years passed, where the only major Norman activity was far away, invading England [Alix: ‘1066 and all that’]!

Roger moved his temporary capital westward to Patralia, and in 1068 the Saracens suddenly confronted Roger at Misilmeri. The Muslims were routed. This time, instead of camels, Roger took their carrier pigeons. He soaked the cloths tied to their legs in Saracen blood, and let them fly back to Palermo: an early example of aerial propaganda. This broke the Saracens’ spirit.

Roger waited for Robert. Robert was back in Apulia besieging the last Greek stronghold of Bari. He he had learned his lessons and amassed a fleet from the Adriatic. He lined the ships across the harbour and tied them together with a heavy chain. In 1071, after four years, a Byzantine fleet arrived to relieve Bari, but the new Norman fleet untied and sailed out to defeat them. It was the Normans’ first major naval battle. Bari soon fell, and it marked the end of more than 500 years of Greeks tenure on the Italian mainland!

With Roger leading the land forces, Robert headed the fleet. First, they took Catania - a strategically important harbour on the east coast - and then headed straight for Palermo. This supreme medieval metropolis, of a quarter of a million people, was an earthly paradise. To capture it would be magnificent in its own right, but it would give the Norman Christians control of the whole island.

Robert won the naval battle against the Saracen fleet, and now famine beset the blockaded population. Rather than wait, Robert pressed for victory and the Normans ultimately succeeded. The Guiscard was not vindictive in victory, and for good reason; such a huge prize needed to be administered, not simply held. And for that he needed the good will of the population. The Saracens were relieved; although they had lost their independence, they could pursue their lives under a strong and benevolent Normal ruler, not under squabbling Emirs.

Robert Guiscard was now officially Duke of Sicily with suzerainty of the whole island, and direct tenure of Palermo. Roger, now Great Count of Sicily, was tenant-in-chief of the rest. Robert then left for his mainland home, never to return. Roger stayed to subdue other areas, such as Trapani.

Guiscard’s Rise and Fall

Robert was kept busy on the mainland. He also got repeated pleas for help from the Byzantine Emperor, Michael. The empire was under increasing attacks, not least by the Seljut Turks. Each plea was more generous, and eventually Robert succumbed to an offer of titles, gold and the promised marriage of Michael’s son to Robert’s youngest daughter, Helena. Robert’s army and navy, in any case, was restless for a new adventure.

But Michael was overthrown, and the deal was off. The new Emperor Alexius didn’t want Robert’s help, but Robert decided to invade anyway, on the pretext of reinstating Michael. Robert suffered naval losses in the Adriatic to the Venetian fleet (loyal to Byzantium), and land losses to the double-headed-axe-wielding English mercenaries, fresh from their loss at Hastings. But the Normans advanced to towards Constantinople.

Robert was forced leave the campaign and return to Italy, to control his unruly Apulian vassals and to answer a plea from Pope Gregory VII. The Pope had just been forcibly displaced with the Antipope Clement III by the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry II, who had marched on Rome.

Robert bided his time and built an army so formidable that, when Henry got wind of it, he and the Antipope fled, leaving the Romans to repel Robert’s Normans. They couldn’t and Gregory was reinstated. This was the pinnacle of Norman achievement: simultaneously they had cowering both western and eastern emperors. But they let themselves down through the terrible pillage that followed. Rome was burnt!

Robert left with an embarrassed Gregory, leaving Clement in residence. Robert returned to the Greek campaign, which he had left to Bohemund to lead, but progress had halted in his absence. In the end, his campaign was defeated by a different enemy: typhoid.

The Guiscard succumbed and died in 1085. He was succeeded by his eldest legitimate son, Roger Borsa. Bohemund was ill and sent to Apulia to convalesce, but then fought a civil war against Borsa, contesting his father’s succession. The civil war only ended when Pope Urban II announced the First Crusade, and Bohemund and many other young and frustrated Normans headed east to win fame and fortune. Bohemund was one of the most successful and was to win title of ‘Prince of Antioch’.

Embryo of a Kingdom

Meanwhile, back in Sicily in 1072, although Roger’s forces were small, he had time on his hands. And he wisely used a variety of tools to secure his new prize: tolerance; diplomacy; Christian colonisation; fairness (e.g., equal taxes for Christian and Muslim alike, making Arabic an official language); and annual conscription. In fact, he secured an elite band of Saracen troops. Many Saracens, who had fled to Africa or Spain, returned to Sicily to resume their lives. A bigger issue for Roger was local Greek resentment at the Latinisation of the church. But he bought them off with gifts.

1077 had seen the collapse of the last two Saracen strongholds in the west; Trapani (Missy Bear’s next port of call) and Erice (our next land-based day trip). At the time of Robert’s death, thirteen years later, Roger was besieging Emir Bernavert in Syracuse. Bernavert had been a thorn in Roger’s side, by raiding Calabrian towns and even kidnapping nuns for his harem. Roger needed to deal with Bernavert quickly, to avoid religious tensions arising. In the naval battle at Syracuse, a fully armoured Bernavert fell into the sea and drowned [Alix: Remind me not to wear my full armour when we cross to Sicily]. His followers lost heart and the besieged city eventually fell. In 1087, even the impregnable citadel of Enna was finally taken, albeit through diplomacy, in 1087.

Possibly because Roger governed a multi-faith land, and maybe even liked his Muslim vassals, he declined to take up Urban II’s call in 1095 for a Crusade against the infidel in the Holy Land.

Count Roger died at his castle at Mileto on the mainland in June 22, 1101. His legacy was the stable land of Sicily enjoying a harmony unparalleled in that age.

Before he died his third wife, Adelaide, had born him an heir, Simon and second two years later, whom they had named Roger. Simon died young leaving Roger II (the nine-year-old bother) as Count of Sicily.

It was the Regent Adelaide who fixed the capital at Palermo. She wisely left the running of the land to her late husband’s able administration, and focused on raising her sons as Sicilians, rather than Norman knights. She made one big mistake, however, when she accepted the new King of Jerusalem’s offer of marriage. Baldwin was a Frank and had just won his title in the First Crusade. He needed the Regent’s immense dowry for funds. But after Baldwin had spent her money, he discarded her and she returned, humiliated, to Sicily. Baldwin also reneged on the deal that, in lieu of further children, Roger would succeed him as King of Jerusalem. Roger never forgot this.

This Norman Conquest, benefited Roger in two ways: first, many Norman malcontents had left on the First Crusade; second, Christian trade with the Levant now boomed, and shipping often used the Sicilian ports and the Straits of Messina as a stepping stone.

As Roger’s power and wealth increased, to protect these assets he strengthened his navy. He was now able to eye Africa covetously. He had conquered Malta previously, and now thought to invade Africa, partly in retaliation for Arab attacks on coastal Calabria. Unlike his predecessors, Roger II preferred not to get his own hands dirty. He did not sail with his fleet, leaving his Admiral in charge, and the campaign ended in disaster, and a huge propaganda win for the Arabs. Africa would have to wait.

Unification and Coronation

Meanwhile on the mainland, Roger Borsa proved to be a weak leader. His lands became ever more chaotic, and he constantly sought his cousin Roger’s help. When Borsa died, as did Bohemond soon after, Borsa’s young son, William, succeeded him, and the situation grew even more chaotic. The cost of Roger’s ongoing help rose. The highest price he sought was when it became known that William could expect no children. Roger demanded the he became William’s heir and William accepted.

William died in 1127, but he had kept a secret from Roger: that he had bequeathed his dominions to the Holy See! Roger had to act fast, and presented Pope Honarius with a fait accompli by leading an army and fleet to Salerno and demanding that he be anointed ‘Duke of Apulia’. Thus incensed the Pope, who gathered an alliance including some of Roger’s own vassals. The forces met somewhere in Calabria. Roger’s force was already entrenched on the higher ground, but he refused to attack; he was clever tactician and always preferred solutions other than bloodshed. As the weeks passed, the Pope’s alliance became restless, and he realised that it would soon break up. So, he sought to negotiate with Roger. All Roger wanted was investiture as Duke of Apulia, under papal suzerainty. This was a massive climb down for Honarius, but he had no choice and agreed. Later, on a bridge outside Benevento, he invested Roger with lance and gonfalon. Once again, Apulia, Calabria and Sicily were united under one ruler.

In 1129, Duke Roger assembled all his bishops, abbots and counts to a court at Melfi and made all his vassals swear a momentous oath: first, they swore fealty the duke and his sons, ensuring his succession; second, they swore to end private wars and to end their right to feud; and third, they swore to surrender any wrong-doers to the Duke’s Courts.

In 1130, yet another papal argument offered Roger another magnificent opportunity: the Antipope Anacletus asked for Norman assistance in his fight against Innocent II, who had succeeded Honoruis. All Roger wanted in payment was a royal crown! Anacletus agreed and later issued a Bull to the effect that Roger’s Crown comprised Sicily, Calabria and Apulia, plus the Principality of Capua and the ‘honour’ of Naples (which was independent and not the Pope’s to give). King Roger II was crowned in Palermo on Christmas Day, 1130, and reigned successfully for another twenty-three years.

And so, the heir of a family of marauding Viking brigands from Normandy, had succeeded in unifying all Norman lands in the south into a single Kingdom, sitting powerfully at the fulcrum of eastern and western churches and imperial powers. He had introduced law and order, through the oath that he introduced for his vassals. And although Roger II knew that an iron fist was vital, his multi-cultural Sicilian upbringing had taught him the value of the velvet glove of patience, bribes and negotiation.

Keep going like this and you could be a history teacher!