The Island of Pelops

- Richard Crooks

- Apr 23, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: May 12, 2022

We are moored alongside at Kiparissia, next to ‘Money Penny’ and ‘Blue Eyes’ (our Belgian sailor friend, Daniel). We had a lovely sail down from Katakolon, accompanied only by the odd shearwater swooping low over the waves kicked up by the morning’s katabatic wind, dropping down off the Peloponnesian mountains to the warmer sea below.

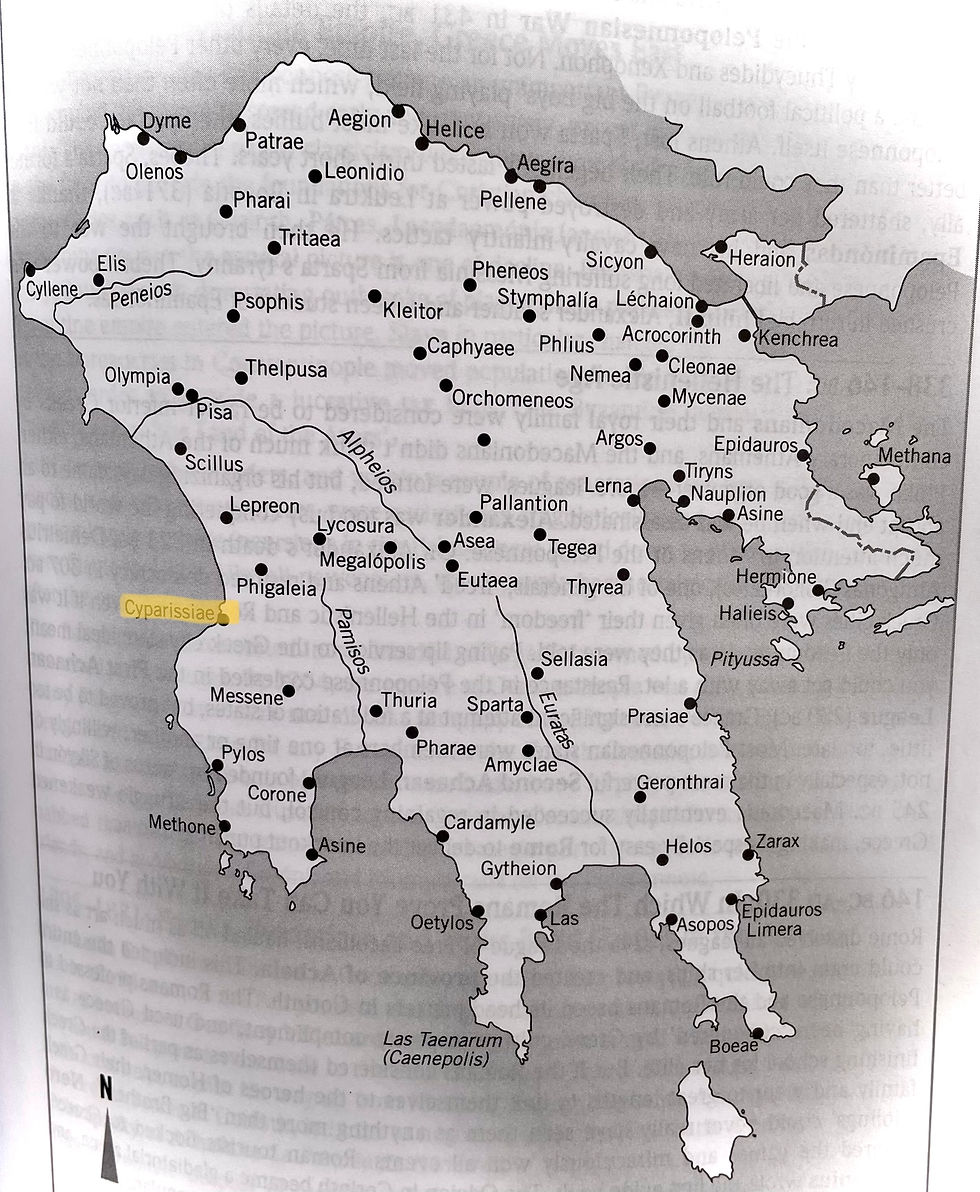

Kiparissia means cypress tree. The town is nestled in a natural amphitheatre below the high, wooded and pointy-topped mountains behind. The medieval castle perches on a rocky ledge half way up, overseeing the waters below. There are a few tell-tale, cigar-shaped cypress trees dotted around. But that is true of most of the landscape around this 3-fingered “island” of Pelops.

When we ran the flotilla out of Poros in 2004, 'Evensong' – the mother duck – would race ahead and help guide the following ducklings to their nest for that day. One day we had a straggler duckling. They did not appear on the horizon. We eventually got hold of them by VHF and politely enquired if they were OK and would be joining the rest of the brood. They were lost. Ah. What could they see on land? Hold on a moment. A long pause. They eventually informed us that they could see, not the anticipated settlement or prominent headland, but some cypress trees! Well, that didn’t help narrow it down much. We eventually got their latitude and longitude and guided them safely home.

Kiparissia is the port of the ancient polis of Messene, which apparently was the first city ever to be planned on a grid-pattern. [Ed - correction, I have subsequently found that not to be true] There are expansive plains of more level ground near the coast and evidence of horticulture. This area – Messenia - is famous for its olives, especially the pointed purple ones from Kalamata, further south. The area is also famous for its figs, but it is not the season for them yet. There are a few small, hard ones on the trees.

But the plant that Messenia was most famous for was the mulberry tree, which would have been used for nurturing silk worms. The groves were planted by the Byzantines and greatly encouraged by the mercantile Venetians. In fact, this island was known in medieval times not as the Peloponnese, but as Morea, which means mulberry. I haven’t spotted a mulberry yet. This may be poor observation on my part, but partly because these valuable trees were systematically destroyed by the Turks and their Egyptian chums during the War of Independence. Remember, it was the Egyptians appearance on the European mainland that got Britain involved in the war, along with France and Russia.

We walked with Judith and Al up past the modern town and climbed further up to the charming medieval quarter. There are actually half-timbered buildings up there with wooden slatted shutters. Most are in need of some love. If you saw one in isolation and out of context, I don’t think you would have guessed it was in Greece? There are winding streets and charming little squares, including one outside the entrance to the castle (which was closed).

Never mind, the views were great, and the square was shaded by an old eastern plane tree (Platanus orientalis). It is called the ‘Plane of Arcadia’. Although Arcadia is a separate region of the Peloponnese (central and to the east), during the southern migration of the Slavs in the 6th and 7th century, Greek Arcadians were displaced to Kiparissia, which was renamed Arcadia. Byzantium called the Peloponnese the ‘Island of the Avars’. The immigrants were assimilated by the empire, and probably spoke Greek. Many Peloponnesian place names had Slavic origins, but those names in turn were changed to Greek ones during the cleansing of Greek independence.

The castle was built by the Byzantines probably using the rubble from an ancient acropolis on the same site. In 1205, the castle was was occupied by the Franks, after the sacking of Constantinople and the formation of the rump state called the Principality of Achaea. But the Franks didn’t stay too long and by 1430 it became part of Byzantine Despotate of Morea. There it remained until its occupation by the Turks in 1460. A square building in the south-eastern corner was a small mosque, but I couldn’t tell that now. According to my Cadogan guide (‘Greece: the Peloponnese) a “Turkish traveller Evlivia Tselebi, in 1668, mentioned 80 houses in the castle.”

Greek life under the Ottomans was not great. The locals were basically tax-farmed by the Ottomans, who didn’t really invest in the region. At Arcadia, there is another sorrowful tale that reminded me of the Suliote women in Epirus who threw themselves off a cliff rather than give themselves to their Turkish rulers. There is a famous Greek folk song - The Plane of Arkadia – which tells the tragic story of Eleni Chameri and her fiancé, Avgerinos Houndras, who were put to death after the beautiful young girl refused to marry the local Ottoman ruler, the Aga of Arkadia! Conflict, death and sorrow seems to be a constant theme running through Greece’s long, turbulent history. And it’s Easter Sunday tomorrow.

The complicated factional history means that Greeks rarely come together for a united cause, because there are always groups warring in the wings. Maybe this goes back to the innate tensions of the polis all those years ago? Or maybe it’s the existence of local klepht warlords who have bravely resisted any occupying force, by waging guerrilla warfare from the mountains.

A classic example of this is to be found at the castle where there is a fine bust of a chap called Gianakis Gritzalis. He had fought against the Ottomans in the War of Independence. So, he should have been a hero, when part of Greece was liberated? But, after western powers eventually installed a Bavarian price – Otto – to reign over the fledgling nation, the warlords who were expecting the spoils of their successes were to be disappointed.

So Gritzalis organised a Messinian Revolution against the German regent in 1834. He demanded more political rights and less maltreatment of the Greek people. Gritzalis failed and was captured and executed in the same year that his revolution had begun. His last words were ''In vain, I die my brothers, because I fought for Greece''.

It sort of reminds me of the German austerity imposed on Greece after their financial crisis.

As I sit here in the cockpit bobbing gently on a glassy sea at sunset, and gazing up at the castle, it is easy to think that Kiparissia - like many other Peloponnesian coastal towns - are peaceful heavens-on-earth. But my reading jolts me to remember that Missy Bear’s Greek voyage is the briefest snapshot on the long historical timeline, and that Alix and I are incredibly lucky to be able to enjoy this calm moment in time.

Comments