The Norman Conquest

- Oct 1, 2021

- 18 min read

Updated: Nov 17, 2025

No, not that one!

I never really enjoyed history lessons at school. Maybe it was the subject matter, maybe the teacher. Anyway, I dropped the subject at 13 years old, before ‘O’ level. But now I love history and would have loved to study it more. I never really had (i.e., never made) the time, when I was working.

I’m sure that my experience is not unique. It’s one reason why I think that some education is wasted on the young. They are also often simply too young to appreciate the learning points from the subject. To my mind, it would be better to give schoolchildren a few ‘education-vouchers-for-life’, that they could cash in during their working career. I would have loved to have had a history voucher, which I could have used during 6-months unpaid leave, whilst receiving a basic state income. They could spend their lessons up to Year 9 learning more practical stuff. You know, nuclear power engineering, HGV driving etc…

While reading various books in Aubeterre, I have been looking for a connection to our next sailing destination: Sicily. This is simply an excuse for writing a new blog, that actually relates to our nautical adventure. As a child, one of my favourite programs was James Burke’s ‘Connections’. [Alix: Oooh, I liked him and he was quite dishy too, wore black a lot] Burke questioned the linear view of history and innovation, and he proposed instead, that the modern world is the result of a web of interconnected events, each one with no prior concept of the final outcome.

Could I find a connection between Aquitaine, where I sit now, and Sicily? The answer is, not really. The examples I found are a bit spurious:

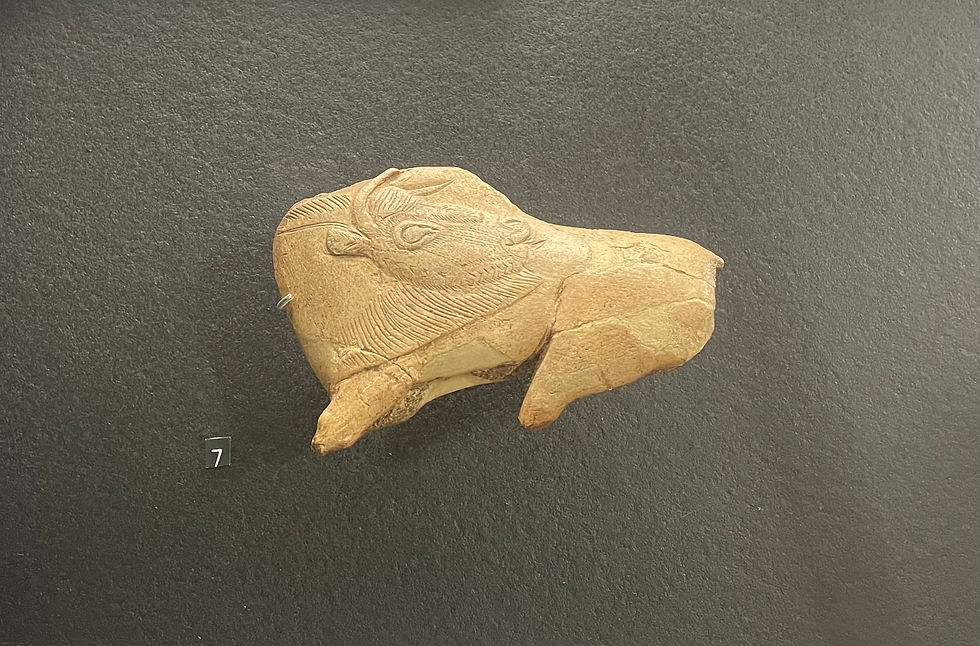

For example, we visited the 'Musée National de Préhistoire' in the Vézère valley this week, to search for a specific artefact that was discovered at the troglodyte village of La Madeleine, that we had visited the previous week.

The artefact is an exquisite stone-age carving on reindeer antler, of a bison licking its flank. It is a remnant part of an arrow-thrower.

During our visit, we passed a display showing the possible migrations of early Homo species from east Africa. As well as the well-known exodus route through the Arabian Peninsula, other possible land bridges might have existed between Africa and Spain (near Gibraltar), and also between Africa and Italy (via Sicily). I think this theory is now also backed up by genetic analyses.

It got me wondering whether the ancestors of that early hominid carver in France had migrated through Arabia, Spain or Sicily?

See, I told you it was tenuous! James Burke would have thrown out the idea out without a second thought.

I was more successful, however, in finding a connection between dear old Blighty and modern Sicily, thanks to a wonderful book called ‘The Normans in the South’, by John Julius Norwich. I’ll embellish below, but if you are not interested in how fecundity, greed, opportunism, brigandry, theft, cunning, bribery, deceit, religion, and other such vices shaped our world, then stop reading now!

The Connection: Harold Hardrada

One fact that I do remember from my junior school history lessons is the main reason why Harold Godwinson (King Harold II) lost the Battle of Hastings to the Norman, William I. No, not the arrow in the eye! I remember that Harold and his army were probably exhausted, following their forced-march up to Yorkshire and back, to fight off another Norseman, Harald ‘Hardrada’ Sigurdsson, who also claimed the English crown.

That battle took place at Stamford Bridge, where we often stopped in the ‘70s enroute to our annual family holiday to Scarborough. The story at school leapt quickly back to William the Conqueror, who had sailed from French Normandy. [DN - The Normans forefather, Rollo, had secured the fiefdom of Normandy in 911 from the Charles, King of the West Franks (who later became known as the French). Charles hoped this would keep these vikings under control.]

But what of Harald Sigurdsson? Who was he? I don’t remember school lessons covering that. After a royal power struggle in Denmark and Norway in 1030, Harald was exiled. He travelled to Constantinople, via Kievan Rus (modern Belarus, west Russia and Ukraine), a land then ruled by Viking settlers called 'Varangians'.

Harald joined the Varangian Guard in Constantinople, which was an elite unit of the Byzantine Army. The unit served as personal bodyguard to the emperor of the Eastern Roman (later known as Byzantine) Empire. Apparently, the emperors liked mercenaries, such as Norsemen and Anglo Saxons from England, because they had no local political loyalties, and could be relied upon to suppress local revolts.

In 1038. the Byzantines sent an expedition to recapture Sicily from the Arab Muslims (Saracens). The taskforce was led by the Greek, George Maniakes. Harald served in that Byzantine force, also alongside Norman mercenaries (i.e., from Normandy), who were also on the Byzantine payroll. Or they were at least expecting some spoils of war. That this invasion was ultimately unsuccessful is of no consequence to this story right now.

But it is that connection – the meeting in Sicily of two distinct tribes of Viking mercenaries (Normans and Varangians) – that led me to ask how convergence happened. And how it happened nearly 30 years prior to the Norman conquest of England, and nearly 60 years before the First Crusade.

Norman Qualities

We have touched on Harald’s route to Sicily, but what of the Normans’ route? (I use Norwich’s excellent book as my information source). First, as some background, it seems to me that the Normans had some qualities, that explain a lot of what happened next:

I) they were pretty fecund, i.e., they had lots of (male) offspring;

II) the first heir seemed to inherit all the existing assets, leaving younger siblings to be provided for;

III) they were materialistic warriors, not innovators or administrators (bar collecting taxes from the serfs). In other words, they didn’t grow wealth, but searched for it and took it by force, which they were ruthlessly good at;

IV) despite their internecine squabbling, they identified and stuck together as French-speaking ‘Normans’;

V) they were opportunistic and quick to spot, or break, alliances, as it suited them;

VI) they tended not to pick a fight that they couldn’t be confident of winning; and

VII) latterly they liked legal systems, because they could make laws that suited them, in the knowledge that most serfs will adhere to laws;

VIII) they were newly Christians, even perhaps God-fearing, in so much as they could ultimately try and avoid hell.

A Rootless Beginning

It is the last point that explains the story's beginning. A semi-mythical event occurred in 1016, at the shrine at Mount Gargano in Apulia (the heel of southern Italy). About forty Norman knights were visiting the shrine [Alix: You can imagine it, beer, T-shirts saying ‘We’ve Been on a Pilgrimage’, with dates on the back], on their way home from their main pilgrimage to Jerusalem [DN - this is way before the First Crusade]. They were approached by a Lombard called Melus. [DN - The Byzantines had recaptured much of southern Italy from the Ostrogoths, but the land had been heavily populated by a new wave of long-bearded Germans - the Lombards.] Melus wanted rid of the Byzantines and their heavy taxes. Would the Normans help him?

The Normans could not resist the opportunity, and would help rid the area of non-Latin church. As pilgrims they were not fully armed, so they first rode back to Normandy to collect arms, and to recruit some of their young male relatives. They returned the next summer, and a year later the Greeks had been driven from the area.

The Greeks returned, however, this time with their infamous Varangian Guard in support, and defeated Melus’ Lombards. The Normans looked for new Lombardian paymasters, and some even joined the payroll of the occupying Greeks. Self-interest drove them, there being no sense of a Norman ‘nationality’ at that time (there were so few of them).

The Greek occupation worried the Pope in Rome, and the German Holy Roman Emperor . The Greeks had captured one city and killed all the Lombard resistance, sparing the Norman contingent was spared, possibly at the behest of the Normans fighting on the Greek side.

In 1021, the Holy Roman Emperor launched a campaign southward against the Greeks. This proved inconclusive, largely because of the Normans on the Greek payroll. Equally, Henry was grateful to other Normans for helping him capture Capua (near Naples) from the Lombards, taking Pandalf prisoner. The Normans had mastered the art of being on the winning side!

Pandalf was released by the emperor's successor, and the former immediately set about recovering Capua. A Norman group, led by Rainulf, offered assistance and helped capture the city for Pandalf. The city folk suffered vengeance, but the Norman garrison was spared, probably at the request of Rainulf.

The First Foothold

Pandalf knew that he he needed Norman muscle to consolidate his territorial gains, and approached Rainulf, who had the largest Norman band. But Rainulf realised that an all-powerful Pandalf would not serve Norman interests in the long-term. So, he switched sides to serve a man called Sergius, helping him retake Naples in 1029. As a reward, Sergius granted Rainulf the town of Aversa (just north of Naples), and also his sister’s hand in marriage.

This was a key moment for the Normans: it was first fief of their own, 13 years after their arrival in Italy to help Melus. This sowed the idea of them becoming established landowners, rather than just being rootless brigands for hire.

True to form, Rainulf showed immediate treachery by switching sides when his wife died, and then accepting Pandalf's offer to marry his niece, along with more land at Amalfi. But when the emperor came south to deal with the troublesome Pandalf, Rainulf swapped sides again. and as a reward the emperor made Rainulf the 'Count of Aversa'. The Normans had climbed a rung up the ladder.

The Normans, back home, had watched how Rainulf operated, and they learned well. Tancred, a Norman from Hauteville on the Cherbourg peninsula, had twelve(!) sons by two wives. In 1035, the first of them rode to Italy seeking the promised opportunities.

Gaining Land and Titles

Meanwhile, the Byzantine Greeks were plotting to retake Sicily from the Arab Muslims. [DN - This was the campaign of 1038, that Hardrada took part in.] George Maniakes stopped in Salerno to ask for help from Gaimar. As Gaimar was starting to have problems managing his young and restless Normans, he readily offered up 300 of them (including the Hautevilles). The campaign ended prematurely when Maniakes was recalled to Constantinople.

Fed up with subsequent Lombard infighting, the Normans decided to elect their own leader. Tancred’s third son - William ‘Iron Arm’ – was duly elected. They called him a count, but he needed a suzerain for formalise it. Gaimar agreed, and William ‘Iron Arm’ was confirmed as ‘Count of Apulia’. Gaimar was himself proclaimed by the Normans as ‘Duke of Apulia and Calabria, and he gifted individual Normans lesser baronies, including 'of land yet to be conquered'.

The Normans were now entrenched and legalised, albeit not yet ratified by the ultimate suzerain, the Holy Roman Emperor.

Papal ‘Recognition’

In 1046, new Normans were still arriving from France.

They included Richard (Rainulf’s nephew), and Robert de Hauteville (Tancred’ sixth son), who was later to be known as ‘Guiscard’, the ’Cunning’.

William ‘Iron Arm’ had been succeeded by Drogo, but he refused to ennoble his brother Robert, nor give him land, for fear of upsetting more deserving local Normans.

Eventually, Drogo sent Robert to command one of the garrisons in Calabria, established following a recent expedition. Robert survived, as Normans did, through brigandry: they simply took by force or ransom from the coastal Greek population, including monasteries.

Richard was not given a free lunch either, so he made a nuisance of himself, living off his wits, until he eventually was acclaimed 'Count of Aversa', following his uncle Rainulf’s death.

The Normans’ behaviour made them increasingly unpopular with everyone: the local Italo-Lombards; the Greeks; and the neighbouring papal states. So much so that Drogo was assassinated, and his suzerain Gaimar was also murdered. Missives were sent to the Pope and Holy Roman Emperor to intervene against the Normans.

Eventually, in 1053, Pope Leo managed to assemble a combined German and Italian army (without the emperor’s help), and marched south. He intended to join forces with a Byzantine army heading north through Apulia. The Normans, led by Humphrey de Hauteville (who succeeded his brother Drogo), included Robert Guiscard’s knights, plus those of Richard of Aversa. They met the papal army at Civitate, and preventing the Pope rendezvousing with the Greeks.

The Normans scored a decisive victory, and - slightly embarrassed that they had fought the 'Vicar of Christ' - escorted the Pope back to Benevento. They only released him once he had formally recognised all the Norman conquests to date. Civitate was as significant to the Normans as Hastings would be thirteen years later!

The Normans (Guiscard specifically) realised their strong position and made impressive gains in Apulia and Calabria. Humphrey de Hauteville died in 1057, and his brother Robert Guiscard succeeded him continuing his ways alongside his Norman rival, Richard.

Both eastern Orthodox and western Latin churches knew they must work together to stop Norman ascendency. But they had significant religious differences, and in 1054 they achieved lasting separation. The main issue was the filioque: the western church adapted the Nicene Creed (which made Jesus, as well as God, an origin of the Holy Spirit!); but the eastern church could never agree to it.

The western church was also embroiled in an internal row between the 'old guard' and the 'reformists' (reformists wanted Papal supremacy, and for Cardinals to elect the Pope without requiring the emperor’s approval.) The reformists won the first battle, and aimed to expel the old Benedict X - now the 'antipope' - from Rome. They asked the Norman’s for help, and Richard agreed. He led 300 knights to Rome, and captured and imprisoned the antipope.

The Norman-Papal friendship had begun, and the new Pope (Nicholas) went to south Italy in 1059 to confirm Richard as ‘Prince of Capua’. He also confirmed Robert as ‘Duke of Apulia, and of Calabria and of Sicily’, even though Robert had never set foot on the island!!

A Foothold in Sicily - The arrival of Roger

From Robert's new title, it was clear that the Pope aimed to throw the Arab Muslims from Sicily. The Pope could, of course, no longer rely on the imperial army, but he had recruited the Normans instead!

And still more Normans arrived. In 1057, Tancred’s youngest son, Roger, arrived in Calabria, and Robert took him under his wing.

Roger de Hauteville was as capable as his older brother, and together they cleared up some remnant Greek cities, before focussing across the Straits of Messina at their island prize.

They hoped that the significant Christian population would be sympathetic. And they knew that the three Emirs were infighting, so that alliances could be made. But, what at first sight looked like a straightforward conquest, would eventually take thirty-one years. There were several reasons:

First, Apulia was not totally secure from Byzantine sorties;

Second, their Calabrian vassals and serfs rose continually in rebellion. This meant the Normans were always fighting on two fronts, which eventually led Robert to focus on the mainland, leaving young Roger to focus on Sicily;

Third, although they could win individual sieges and battles, the Normans lacked numbers, so they could not hold their wins, whilst advancing to take the next city. The Sicily campaign also depended upon a bridge-head, and a secure supply line back to Calabria;

Fourth, not all the island Christians regarded the Normans as being better potential masters than the Saracens; and

Finally, the Normans had no navy, which was severe handicap when trying to besiege coastal towns on an island.

Roger’s campaign began properly in 1061, when one of the Emirs – Ibn al-Timnah - asked him to come to his assistance. Roger had a couple of early setbacks, but he took Messina the following year, before Robert arrived with help. With their friendly Emir, they headed westwards towards Enna, the stronghold of Emir Ibn al-Hawas.

Roger managed to coax the Arabs from the city and routed them in the field. The hostile Emir remained safe in the citadel, and watched on as the Normans scorched his lands, plundered and frightened his people into paying homage to them. The siege of Enna ultimately failed, and many Normans returned to the mainland for the winter. But crucially, some remained and built the first Norman castle on the island, at Aluntium.

Because Roger was so capable, Robert had become jealous, and the brothers’ quarrels delayed their Sicilian campaign. One quarrel regarded inheritance:

Robert had only a bastard son, Bohemund. So in 1058 he married a formidable Lombard warrior called Sichelgaita, who bore him eight children, including three male heirs.

Roger also took a wife, his childhood sweet-heart, Judith of Evreux. She was the daughter of a first cousin of William the Conqueror. Robert did not want Judith to have a dowry upon Roger’s death, that might give her Sicily. Roger was furious, but won the ensuing fight with his brother.

He returned to Sicily with Judith to find that his Emir ally had been assassinated, and the whole situation was unstable. The local Greeks also rebelled and tried to capture and ransom Judith.

Roger returned in time, but his Normans were now besieged by both Greeks and Arabs. They held out over the long, cold winter, even eating their own horses [Alix: We have a cheval butcher in our local town in France]. At the point of starvation one cold January night, Roger attacked the Arab sentries, who were asleep after drinking local red wine. The siege was over.

Sicilian Crusade

The Normans re-grouped and then won a decisive battle at Cerami. Roger sent four captured camels to the Pope in Rome. In return, the Pope sent Roger a papal banner, and absolved from sin anyone who joined Roger and Robert in Sicily. This campaign was now effectively a Crusade, and 30 years before the 'First Crusade'!

At this point the Pisans, annoyed by ongoing Arab piracy, appealed to Roger for land-based assistance to capture Palermo. Roger declined: perhaps he wasn’t ready; or maybe he did not trust the Pisans’ long-term objectives.

Instead, in 1064 and with Robert’s help, the Normans headed straight to Palermo and besieged it. It was to no avail, however, as without a navy the Normans could not prevent the free-flow of shipping into the harbour.

Stalemate was broken in 1068, when the Arabs suddenly confronted Roger at Misilmeri, but were routed. This time, instead of camels, Roger took their carrier pigeons and soaked the cloths tied to their legs in Arab blood. He let them fly back to Palermo, in an early example of aerial propaganda. This broke the Arab’s spirit.

Roger waited for Robert, who was back in Apulia besieging the last Greek stronghold of Bari. He had amassed a fleet from the Adriatic, and he lined them across the harbour, tied together them together with a heavy chain. In 1071, after four years, a Byzantine fleet arrived to relieve Bari, but the new Norman fleet untied, and sailed out to defeat them.

It was the Normans’ first major naval battle. Bari soon fell, and that marked the end of more than 500 years of Greeks tenure on the Italian mainland!

With Roger leading the land forces, and Robert heading the fleet, they took Catania, and then headed straight to Palermo. This supreme medieval metropolis, of a quarter of a million people, was an earthly paradise. To capture it would be magnificent in its own right, but it would give the Norman Christians control of the whole island.

Robert won the naval battle against the Arab fleet, and blockaded the city. Famine ensued, but rather than wait, Robert pressed for victory, and the Normans ultimately succeeded. He was not vindictive in victory. And for good reason: such a huge prize needed to be administered, not simply held, and for that he needed the good will of the population.

Robert was now officially 'Duke of Sicily', with suzerainty of the whole island, and direct tenure of Palermo. Roger, now 'Great Count of Sicily', was tenant-in-chief of the rest. Robert departed for his mainland home (never to return), leaving Roger to subdue the other areas.

Robert's fall

Robert was kept busy on the mainland, where he also got repeated pleas for help from the Byzantine Emperor, Michael. The empire was under increasing attacks from the Seljuk Turks. Each plea was more generous, and eventually Robert succumbed to an offer of titles, gold and the promised marriage of Michael’s son to Robert’s youngest daughter, Helena. Robert’s army and navy, in any case, was restless for a new adventure.

But Michael was overthrown, and the deal was off. The new Emperor Alexius didn’t want Robert’s help, but Robert decided to invade anyway, on the pretext of reinstating Michael. Robert suffered naval losses in the Adriatic to the Venetian fleet (loyal to Byzantium), and losses on land English mercenaries, fresh from their loss at Hastings.

Nevertheless, the Normans continued to towards Constantinople. Robert was forced leave the campaign, and return to Italy to help the Pope fend off a new antipope. Robert was successful, but his men let themselves down through the terrible pillage that followed. Rome was burnt!

Robert returned to the Greek campaign, which he had left his son Bohemund to lead. Progress had halted in his absence, and the campaign was defeated by a different enemy: typhoid. It is thought that Robert died in 1085 at Fiskardo, on Cephalonia

He was succeeded by his eldest legitimate son, Roger Borsa. The bastard, Bohemund, was ill, and sent to Apulia to convalesce. but he then fought a civil war against Borsa. The civil war only ended when the Pope (Urban II) announced the First Crusade: Bohemund and many other young and frustrated Normans headed east to win fame and fortune. Bohemund was one of the most successful. and was to win title of ‘Prince of Antioch’.

Roger's Rise - Embryo of a Kingdom

Back in Sicily in 1072, although Roger’s forces were small, he wisely used a variety of tools to secure his new island prize:

tolerance;

diplomacy;

Christian colonisation;

fairness (e.g., equal taxes for Christian and Muslim alike, making Arabic an official language); and

annual conscription.

In fact, Roger secured an elite band of Arab troops (Saracens), who had returned to Sicily from Africa to resume their lives. But a bigger issue for Roger was local Greek resentment at the Latinisation of the church. But he bought them off with gifts.

Possibly because Roger governed a multi-faith land, and maybe even liked his Muslim vassals, he declined to take up Urban II’s call, in 1095, for a Crusade against the 'infidel' in the Holy Land.

Count Roger died at his castle at Mileto on the mainland in June 22, 1101. His legacy was the stable land of Sicily enjoying a harmony unparalleled in that age.

Before he died, his third wife, Adelaide, had born him a Simon and another Roger. But Simon died young, leaving Roger II (the nine-year-old bother) as 'Count of Sicily'.

It was the Regent Adelaide who fixed the capital at Palermo. She wisely left the running of the land to her late husband’s able administration, and focused on raising Roger a a Sicilian, rather than a Norman knights.

She made one big mistake, however, when she accepted the new 'King of Jerusalem’s' offer of marriage. The crusader Baldwin was a Frank, and he needed the Regent’s immense dowry for funds. After Baldwin had spent Adelaide's money, he discarded her and she returned, humiliated, to Sicily.

Baldwin also reneged on the deal that, in lieu of further children, Roger would succeed him as 'King of Jerusalem'. Roger never forgot this.

The First Crusade did benefit Roger in two ways:

first, many Norman malcontents had left to go to the Holy Lands;

second, Christian trade with the Levant now boomed, with shipping often using Sicilian ports, and the Strait of Messina as a stepping stone.

As Roger’s power and wealth increased, he strengthened his navy. He conquered Malta, and now looked at Africa covetously. Unlike his predecessors, Roger II preferred not to get his own hands dirty. He did not sail with his fleet, but left his Admiral in charge. The African campaign ended in disaster, leaving a huge propaganda win for the Arabs.

Unification and Coronation

On the mainland, Roger Borsa proved to be a weak leader. When he died (as did Bohemond soon after), Borsa’s young son, William, succeeded him, and the situation grew even more chaotic and costly for Roger to support him. When it became known that William could expect no children, Roger demanded he became William’s heir.

William accepted. But he had not told Roger that he had secretly bequeathed everything to the Pope. When William died in 1127 and his secrete came out, the furious Roger had to act fast. He presented the Pope with a fait accompli by leading an army and fleet to Salerno and demanding that he be anointed ‘Duke of Apulia’.

This incensed the Pope, who gathered an alliance, and met Roger's forces somewhere in Calabria. Roger’s force was already entrenched on the higher ground, but he refused to attack. Roger was clever tactician, and always preferred solutions other than bloodshed. As the weeks passed, the Pope’s alliance became restless, and he realised that it would soon break up. So, he sought to negotiate with Roger.

All Roger wanted was investiture as Duke of Apulia, under papal suzerainty. This was a massive climb down for the Pope, but he had no choice but to agree. Later, on a bridge outside Benevento, he invested Roger with lance and gonfalon. Once again, Apulia, Calabria and Sicily were united under one ruler: Roger.

In 1129, Duke Roger assembled all his bishops, abbots and counts to a court at Melfi and made all his vassals swear a momentous oath:

first, they swore fealty the duke and his sons, ensuring his succession;

second, they swore to end private wars and to end their right to feud; and

third, they swore to surrender any wrong-doers to the Duke’s Courts.

In 1130, yet another opportunity arose: the Antipope asked for Norman assistance in his fight against the Pope. All Roger wanted in payment was a royal crown! The Pope agreed. He later issued a Bull to the effect that Roger’s Crown comprised Sicily, Calabria and Apulia, plus the Principality of Capua, and the ‘honour’ of Naples (which was independent and not the Pope’s to give).

King Roger II was crowned in Palermo on Christmas Day, 1130, and reigned successfully for another twenty-three years!

And so, the heir of a family of marauding Viking brigands from Normandy, had succeeded in unifying all Norman lands in the south into a single Kingdom, which sat powerfully at the fulcrum of eastern and western churches and imperial powers. Roger had introduced law and order (through the oath that he introduced for his vassals.) And although Roger II knew that an iron fist was vital, his multi-cultural Sicilian upbringing had taught him the value of the velvet glove of patience, bribes and negotiation.

Comments